Lately I’ve been doing more regular darkroom printing and this has left me in a bit of a slump. Although I love many of the developer formulations I’ve made, they’ve often not been designed explicitly for darkroom printing. EXG1/GVG1 would produce excellent negatives with increased speed, fine grain, etc… but in the darkroom it was often very difficult to get everything on the negative onto the paper without resorting to lith printing. This problem was only slightly improved with GVK1. GVK6 (yet to be published) has significantly improved this problem, but these developers also reflected the time in my life at which they were formulated. I was doing almost exclusively lith printing and with early ModernLith formulations I needed extended scale and moderately high contrast negatives… So GVK1 specifically was formulated with this aim. EXG1 was formulated when my main priority was getting the best scannable negative, which also benefits from a long density range. And now, I’m doing regular darkroom printing a lot, so it calls for a developer with a new aim.

GVM1 is recommended for:

Extremely smoothed portraits of light skinned people in controlled light

High contrast landscape scenes

Pushing film to use it at increased speed without greatly increasing contrast

Taming the contrast of very high contrast materials

Getting all of the image detail onto a print in the darkroom without great difficulty

35mm Ilford FP4+@400, GVM1, dilution A, 70F, 16.5m dev time

Characteristics

GVM1 is a very unique and deliberately designed developer. It is extremely high concentration, yet requires minimal uncommon ingredients and minimal heating of solvents. It is expected to have a very long shelf life despite being a low sulfite formula and containing a phenidone derivative. It was designed with the goal of a more “printable” developer than my previous formulations, while still giving a speed increase and working well for pushing. The final result however is surprising in how unique it is able to render photos. It gives a very particular old fashioned appearance, but with the benefit of modern film, moderately fine grain, and high speeds.

Extremely compensating developer which easily captures all highlight detail even in very contrasty scenes

Excellent at pushing, giving more shadow density relative to highlight density than a developer like D-76. Note that this developer at any dilution is likely not the best for extreme pushes beyond 3 stops from box speed though.

Not recommended for pulling and in some cases even box speed gives poor results due to its speed increasing nature.

Speed increasing. With certain films this developer seems to produce as much as a 1.5 stop increase in speed. Combined with the excellence at pushing, is designed for high speed use when contrast needs to remain fairly normal.

Can be used at 3 different dilutions. A (2+100), B(3+100), and C(4+100). A is for normal to low contrast with restricted dmax. B is for normal to increased contrast and moderate pushing with less dmax restriction. C is for high contrast where dmax is allowed to run away and for the most extreme of pushing. Dilution C is not highly recommended. See note below about dilutions.

Moderate grain. It has an appearance of increased resolution without the image appearing grainy. With big enlargements the grain is visible but often not “pokey”. The grain is smooth and pleasant, especially when processed for box speed or 1 stop faster. Grain tends to build and became more randomized with longer development.

Decreased dmax, even with greatly extended development times. This keeps dmax within a range that the entire image will “fit” onto paper.

Is orange-brown when freshly mixed, but when it goes off, will turn a deep blue or green, giving a simple indication to if the solution is safe to use.

Unlike PQ developers, will not suddenly die. It will decrease in activity once it turns green, but will actually still produce an image. Thus, there is minimal risk to getting blank film due to unexpected aging such as with Xtol

Resistant to fog, even with materials which are easily susceptible to fog. Does not typically exacerbate age related fog.

Can be used to control the contrast of high contrast and alt-process materials without sacrificing speed, including paper negatives and ortho litho film

In tests, shelf life is predicted to be good. Though, this is still untested. I have a batch which I will let age for several months and then measure the curves of, but this of course takes time. Concentrates have survived being left in the open for several days with no change in color or activity thus far. The longevity of the solution may depend also on how fresh the glycin used to make it is.

35mm Ilford FP4+@125, GVM1, dilution A, 72F, 9.5m, on camera flash

Mixing Instructions

Distilled water is highly recommended and gentle heating may be useful, but is not required. Follow these steps in exactly the order given.

1% Dimezone-S Instructions:

First, a 1% solution of Dimezone-S in propylene glycol should be mixed as so:

90ml propylene glycol

1g Dimezone-S

top to 100ml with glycol

This may take a while of stirring, warming will help. NOTE: warming glycol above 140F will cause the glycol to give off non-toxic but highly flammable vapors. Do any heating with care away from open flame and lightly cover the container using foil or filter paper

Solution should be a pale orange once mixed. Expected to stay good for several months if kept in an airtight container and no water is introduced.

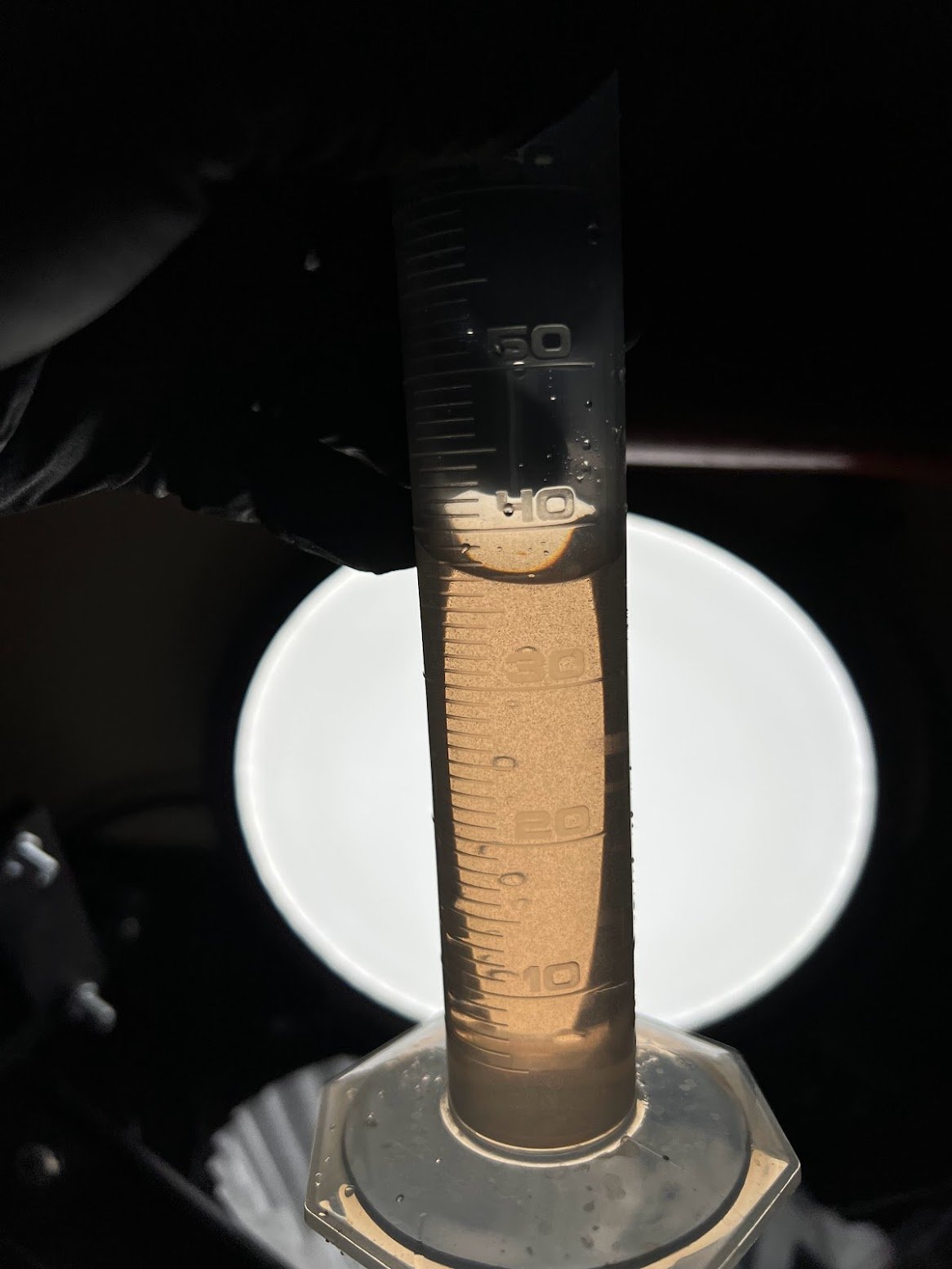

Slurry of GVM1 mixture after adding Glycin but before adding Dimezone and glycol

GVM1 (or GVM1.1) Formula:

To make 100ml of concentrate, used to make between 5L and 2.5L of working solution depending on dilution used

30ml distilled water (highly recommended to use distilled!)

16ml potassium sulfite 45% solution, or otherwise equivalent to 7.2g and 16ml of water (in case using a solution strength other than 45%)

5g sodium metaborate. Note, you do not need to wait for this to dissolve

18g potassium carbonate. The solution will heat up slightly.

Stir until both the carbonate and metaborate are fully dissolved. The solution might be slightly cloudy

3.6g glycin. This will not dissolve, create a slurry. Do not proceed to the next step until all of the glycin is wet and the solution is somewhat frothy and either brown or tan (Depending on freshness of glycin)

34ml of Dimezone-S 1% by weight, dissolved in propylene glycol. Using glycol is absolutely essential here. Solution should go from a slurry to a fully dissolved solution.

top to 100ml with distilled water. (add about 5ml of water)

Solution may appear somewhat cloudy due to very small bubbles in solution. This will clear after a few hours as the solution stands. There should be no dissolved powder at the bottom of the container though.

Use at 2+100 (dilution A), 3+100 (dilution B), or 4+100 (dilution C). A for normal to low contrast, B for normal to increased contrast, or C for high contrast.

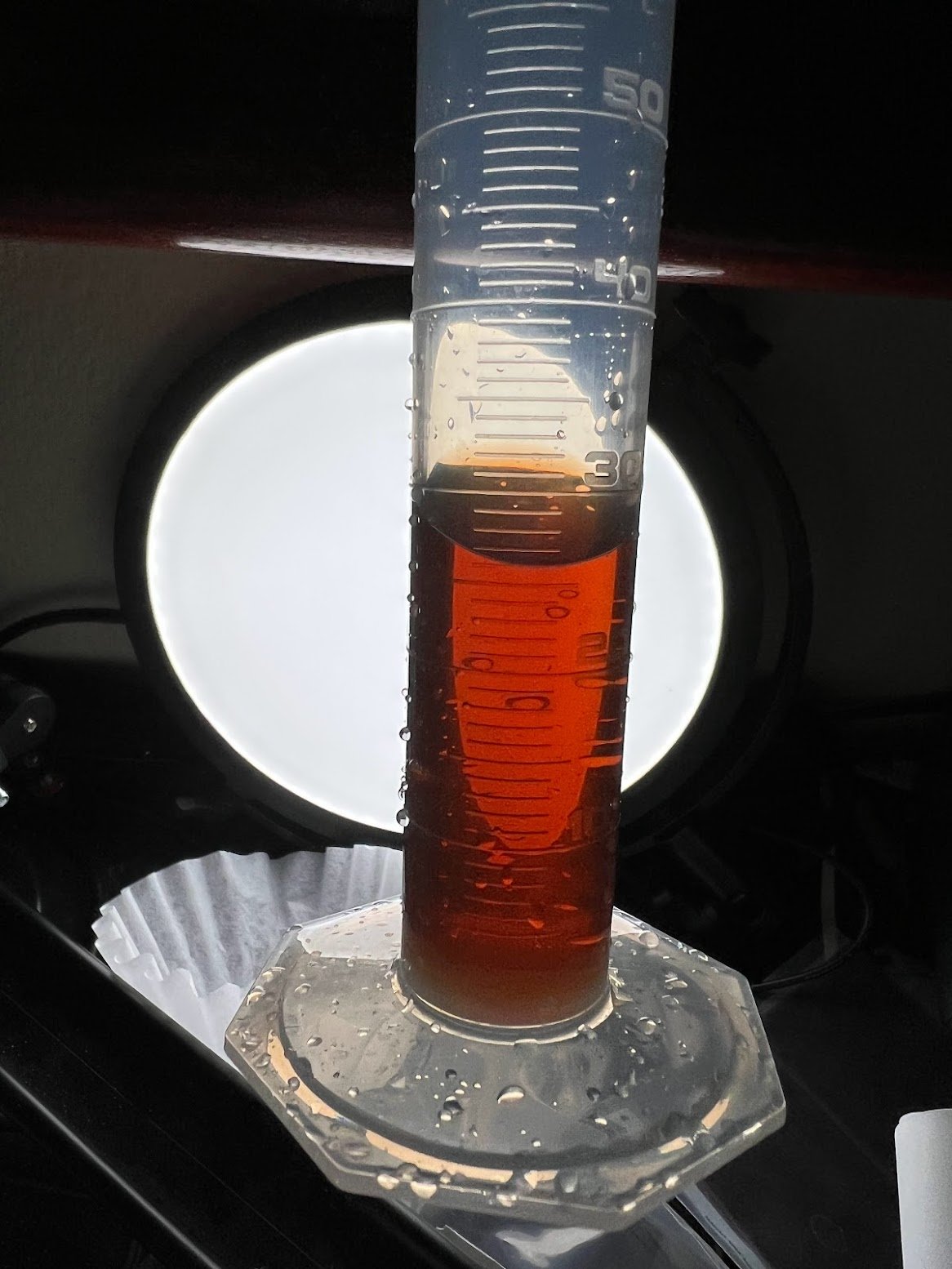

Solution will be a moderately deep tan to a dark orange-brown depending on how fresh the glycin used is. When added to water to make a working solution, no matter the freshness of glycin, will turn a pale iridescent pink-orange. After use developing film, will appear either a deep yellow-green, deep green, or moderate blue, depending on the dilution used and the type of film processed.

UPDATE: GVM1.1 has some minor solubility issues and will produce a small amount of powder precipitate at about 3 weeks of storage. This seems to not make a measurable practical difference, but I prefer to swirl the concentrate a bit before usage to get some of the precipitated crystals into the working solution. To solve this, I’ve formulated GVM1.2, which behaves identical to 1.1, but uses only potassium salts and adjusts solvent amounts

Double-XX @ 500 ISO. One of the first films tested in GVM1.2

GVM1.2 Formula:

First, it is necessary to create a 2% dimezone solution and a 50% potassium metaborate solution.

To create the 2% dimezone solution, follow the instructions above, except use 2g of dimezone in 100ml of glycol

To create the potassium metaborate solution is more complex:

Don proper PPE, especially eye protection and gloves!

70ml of room temperature or preferably ice cold distilled water

51.3g potassium hydroxide — Add VERY slowly and in very small batches. Keep an eye on the temperature. If it becomes too hot to touch, then wait or put the mixing vessel into an ice water bath. This reaction produces a lot of heat!

56.6g boric acid — Add slowly and in small batches, like say 10g at a time. This is not as reactive as the hydroxide addition, but does produce some heat so still be careful.

There should now be a small amount of fluffy clumps in the bottom, this is potassium tetraborate (borax). There is a purposeful surplus of boric acid which should mean this always happens. How much depends on purity of your potassium hydroxide

Add a small amount of potassium hydroxide in order to make the fluffy powder dissolve. Add 0.3g or so at a time. For my batch, I had to add 0.8g of potassium hydroxide

There should be a very small amount of the white fluffy clumps left. If you accidentally added too much hydroxide and there is none, then add a small amount more boric acid

Finally, filter the solution through a coffee filter and measure the amount of solution. Add water to make 150ml of solution, for me this required adding about 10ml of water.

To test the solution, add 1ml of solution to 110ml of distilled water and measure the pH. The pH should measure about 10.

Finally, to mix GVM1.2 concentrate:

50ml of distilled water

16ml of 45% potassium sulfite solution or otherwise equivalent to 7.2g of potassium sulfite and 16ml of water

6ml of potassium metaborate 50% solution

18g potassium carbonate

Stir until completely clear

3.6g glycin. This will not dissolve, make a slurry

17ml of Dimezone-S 2% in propylene glycol (or 17ml of propylene glycol and 0.34g of dimezone-S)

Top to 100ml with distilled water

Use at 20-40ml of concentrate added to 1L of water to make the working solution. Works and looks identically to GVM1.1

One big benefit to GVM1.2 is that due to the better solvent ratios, this can be kept much colder than GVM1.1 without risk of crystallization or precipitates. I’ve kept a GVM1.2 test batch in a 34F/1C refrigerator overnight with no changes. Also since such a small amount of concentrate is used, it can be used while cold without significantly changing the working solution temperature. I highly recommend GVM1.2, but only if you have the proper tools and knowledge to create the potassium metaborate solution safely. Otherwise GVM1.1 will work well despite the precipitate issue.

If the concentrate appears black or dark green, or does not turn pink-orange when diluted, the concentrate should be considered untrustworthy. It will likely still develop film and produce an image, but it is expected to be of lower activity or to have other detrimental effects.

The color changing effects of this developer should be the primary way to judge if the developer is still good.

There is some potential for substituting some ingredients for more easily available ones, but you would likely need to halve the concentration (and thus use double the amount of concentrate for working solution). However, I have not tested these substitutions at all. Substituting phenidone for dimezone-S is also likely possible but a non-trivial endeavor since the two, though related, behave in different ways with different superadditive agents.

An equivalent amount of sodium sulfite is 6g

An equivalent amount of sodium carbonate monohydrate is 20g

If phenidone is substituted, the oxidation colors and behavior will likely be different

Substituting glycin is likely impossible without creating an entirely new formula

Removal of propylene glycol is possible but would involve significantly decreasing concentration, likely by 10x, making it a 1+9 dilution developer. It would also be much more difficult to mix requiring more stirring

Substitution of propylene glycol with ethylene glycol should be possible without detrimental effect, however the solution would then be acutely poisonous.

In situ synthesis of metaborate is possible by using sodium or potassium hydroxide and borax.

35mm Ilford FP4+@400, GVM1, dilution A, 70F, 16.5m dev time

Copyright

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Please do not republish this formula without explicit permission. If you’d like to share this formula, please link to this article instead of copy and pasting the formula: https://grainy.vision/blog/gvm1 . I may commercialize this formula or release this formula to the public domain later on, but for now I’m undecided. This does not restrict your ability to mix and use this formula for personal or commercial photography. I’m only requesting that you do not copy and paste this article somewhere else. I run no ads on this site and operate without monetization.

In general I do not seek to make any significant profits or anything like that from this formula, or film photography in general… but I’m undecided what to do going forward with it at this point. If you’d like to license this formula or make any other kind of deal around this, please contact me by email at “ashley AT earlz DOT net”.

Aging

As the concentrate ages, there is some insoluble white sediment which will fall out of solution. This efffect can be seen even with highly diluted working solutions after standing overnight. This is believed to be an oxidation product, but it is unknown what this product actually is or what ingredient causes it to form. Regardless, there seems to be no harm or difference in results due to this product falling out of solution. It can simply be left to remain in the bottom of the container.

35mm Ilford HP5+@800, GVM1, dilution B, 70F, 14m, on camera flash

Development Times

I list two sets of times. Actual times are ones which were actually run with film and developed results which I liked and which printed well. Estimated times are ones which is what I’d personally use to develop such film judging from how this developer works. It’s very difficult to judge how a new film will react and what the time difference between dilution amounts will be. I highly recommend testing new films with a few test shots first due to this effect. Over development will result in increased grain and often lowered contrast. Most films seem to give 1-2 stops of true speed increase.

NOTE: The times listed for D-76 1+1 is not a very good way to gauge unlisted films, but can be used as a very rough guess for dilution A. For dilution B, take the D-76 1+1 time and multiply it by 0.8. This should only be regarded as a starting point for unlisted films! I’ve personally observed that many films do not work well by following that guide.

FP4+@400

All times are listed at a temperature of 70F or 21C.

Actual Times for dilution A:

FP4+ @ 200 ISO, 12m

FP4+ @ 125 ISO, 10.5m (adjusted from 9.5m@72F)

FP4+ @ 400 ISO, 16.5m (adjusted from 15m@72F)

HP5+ @ 200 ISO, 16.5m (adjusted from 15m@72F) — NOTE: dilution A is not recommended for HP5+

Ultrafine Exteme 100 @ 320 ISO, 12m

1960s era Kodak Plus-X (somewhat fogged) @ 50 ISO, 12m

FPP Direct Positive film: NOT recommended (blank film)

KodaLith type 3 (80s, not fogged) @ 12-25 ISO, 7m (adjusted from 6.5m@72F) — note: 30s initial agitation, 4x agitation per minute

T-Max 400 @ 800 ISO (400-1200 looked good at this time), 10m (adjusted from 9.5m@71F)

Panatomic-X (60s, minimal fog) @ 32-64 ISO, 10m (adjusted from 9.5m@71F)

FN-64 @ 200, 9.5m (note: if using red filter, rate at ISO 400)

FN-64 @ 64, 5.5m (note: if using red filter, rate at ISO 125)

CMS-20 ii @ 50-100, 9.5m (weak shadow detail, not recommended

CMS-20 ii @ 25, 5.5m (note: was a bit over developed, could likely do 4.5m with better results)

FPP Blue Sensitive (6 ISO) @ 6 ISO, 5.5m

Double-X @ 500 ISO (produced good results at 250-1000 ISO), 12m

Actual Times for dilution B:

HP5+ @ 400-800 ISO, 14m

FP4+ @ 200-400, 14m (note: poor shadow detail at ISO 400 in high contrast scenes)

Actual Times for dilution C:

HP5+ @ 3200 ISO, 20.5m

T-Max 3200 @ 1600-3200, 20.5m (note: extremely grainy!)

35mm T-Max 400@400, GVM1, dilution A, 71F, 9.5m dev time

Estimated times for dilution A: NOTE, TEST BEFORE TRUSTING THESE TIMES WITH VALUABLE PICTURES

FP4+@800 ISO, 18m

HP5+ @ 400, 18m

T-Max 400 @ 400 ISO, 8m

Ultrafine Extreme 100 @ 100 ISO, 8.5m

Ultrafine Extreme 100 @ 200 ISO, 10m

1960s era Plus-X @ 100 ISO, 15m

Arista Ortho Litho @ 1.5-0.8 ISO, 8m (tested at 10m, but with poor results due to assuming speed would be closer to 12 ISO) — note: 30s initial agitation, 4x agitation per minute

CMS-20 ii @ 25 ISO, 5.5m

FN-64 @ 125 ISO, 7.5m (note: if using red filter, rate at ISO 250)

Estimated times for dilution B: NOTE, TEST BEFORE TRUSTING THESE TIMES WITH VALUABLE PICTURES

HP5+ @ 400 ISO, 13M

HP5+ @ 800 ISO, 14.5M

HP5+ @ 1600 ISO, 18M

FP4+ @ 125 ISO, 9M

35mm T-Max 3200@3200, GVM1, dilution C, 72F, 20.5m dev time, ambient light

Stand Development

Only minimal testing has been done using GVM1 with stand development. It appears to be subject to bromide drag, but with most subjects this does not seem to actually cause an issue. Expectations:

90 minutes with dilution A is likely a good starting point, but each film will be different. Once again HP5+ seems to react extremely slowly with this developer at dilution A

Using only 1ml concentrate per 100ml of water (half of dilution A) may produce a better contrast curve. I’d recommend using a minimum of 500ml of working solution per roll of 35mm film if using such a small amount of concentrate

Agitating once or twice per stand is highly recommended

Expect increased highlight density

Not recommended for going beyond a 1 stop push

Grain will appear somewhat smoother in appearance, but sharpness is actually increased with edge adjacency effects visible upon inspection

HP5+@400, GVM1, dilution A, 120m stand development, 71F. 1m initial agitation and 20s of agitation at half way

Different Dilutions

I list 3 different dilutions. Each dilution has different characteristics and trading one dilution for another is not simply “50% more active” or “increases contrast by 1 grade”. The different dilutions have entirely different contrast curves and grain characteristics even if all dilutions are related.

My personal recommendation:

Use dilution A unless increased scale and dmax is required.

Look at box speed development times of the film for developer D-76 1+1 at 20C/68F. If the listed time is greater than 10m, then greatly prefer to use dilution B instead of A

Use dilution C only when high contrast or extreme pushing is required.

My personal observations in comparison tests:

HP5+ is a very slow to develop film. In dilution A, even with pulling the results will be incredibly grainy and require very long development times (15m+). In dilution B, the development times are much more reasonable, pushing is much more reliable, and overall grain seems to be significantly smoother.

FP4+ is a faster to develop film and in dilution A seems to give a great contrast curve with ample shadow detail and beautiful midtone gradations. However, in dilution B, highlights are easier to runaway and it takes on a much more contrasty appearance, development speed only seems to be increased by about 10% by using dilution B.

Unfortunately I have not done nearly enough testing with dilution C to highly recommend it or understand how it works. I’d recommend A or B unless you are trying to push beyond 2 stops from box speed or need higher contrast negatives with stronger density.

35mm Kodak Tri-X@400, GVM1, dilution A, 70F, 16m

Printing GVM1 Developed Negatives

GVM1 is a particularly great developer for negatives which you intend to use in darkroom printing. It gives an oddly vintage appearance with strong detailed shadows and gentle subtle highlights. The following are some examples of prints I’ve made.

Grade 2 Print, Kodalith @ ISO 12

Grade 2 Print, KodaLith @ ISO 12 (notice sky detail)

Contrast Curve

This isn’t what i’d call greatly scientific data, but can be interesting to see was part of what guided the formulation. The following are the contrast curves for GVM1 dilutions A and C, compared against GVK6 (a non-compensating glycin-metol developer) and D-76H dilution 1+1.

This chart may take a bit of time to read and understand, but the big take aways that I see are:

for GVM1 2+100 (dilution A), it seems to be quite slow, but when going for the same amount of development, will have ample highlight compensation, but also better highlight differentiation due to having less of a hump compared to GVK6

For GVM 4+100 (dilution C). The developer takes a little bit to get going, but has ample energy to produce a very strong dmax. However, compared to GVK6, it still produces around the same amount of shadow density when development is kept shorter (1m) and actually produces more highlight compensation than GVK6 with short development times.

Both GVK6, GVKM1 A and C both produce measurably better shadow density and speed compared to D-76H. (not listed here, but I also tried D-76H for extended time as well as with no dilution, and neither could produce the speed increase as shown here. I believe this functions as proof that GVM1 is a speed increasing developer. However, with actual modern films, this effect may not occur, or may not happen to the same extent.

The following is an interesting comparison showing how the extremely highlight compensation of this developer can produce drastically different results when the subject’s exposure values lies primarily within this zone of highlight compensation.

History and future of formulation

Note: this section is purely informational

I’ve been a bit disillusioned with my developer formulations. I feel like they were often formulated by throwing something on the wall and seeing if it works. Formulation tests were very much trial and error with little consistency to them. Judging results and differences in formulation was often a difficult exercise to evaluate. This is the first developer which I tried to create a formula with formal measurements of results. I’ll make a separate article about this eventually, but I judged this developer against its peers by using a step wedge, Ilford MGV RC paper, and a densitometer. I have a standard regimen for how to create a series of paper tests which should (hopefully) simulate a film curve, but with the benefit of working on a safe-lit darkroom instead of pure darkness… and is also much cheaper to work with than film. This developer specifically I wanted to make more active than GVK6, without the tendency for highlights to run away beyond what would be easy to print on paper. I wanted a compensating developer in which over exposed highlights would remain within a printable range, even if they did become lower in contrast. I also wanted a moderate grain, high sharpness developer. I wanted something where I could take a picture of a bright sunny landscape and print both the land and the clouds in the sky without too much difficulty. I didn’t expect phenidone-glycin to give me this, but it was what I was running new developer tests with the aim of finding, either that or speed increases beyond what GVK6 would give me. When I got to prototype #3 or #4 of GVM1, the curve started to really take shape and began to show that this formula might actually be possible in the way I want it to be. Around #8 when I removed triethanolamine as a “test that likely won’t work” I found I could create an extremely concentrated formula for this as well without detrimental effect, resulting in a concentrate which i expect to be quite shelf stable.

Although I had this desire to create a developer which would produce great printable negatives, I set out designing GVM1 as an intellectual curiosity first. I’ve often heard that glycin and phenidone are super additive, but that there are no commercial nor popular published developers using this combination of agents and many sources say “there are no formulas which use this”. The only developers formulated with this had much different aims than for regular photography, such as for aerial photography, or rapid processing, and these seem to have only been research curiosities. I had previously attempted to make this combination into a formula but the results were, while attractive in terms of grain structure, also had an ugly, blown out, rendering of highlights, produced a speed loss, had fogging issues, and had a very weak dmax. So I had mostly assumed at that time that phenidone and glycin are rarely used together for a reason. I often am seeking to cure the impossible, so I figured it was time to revisit it, but this time using Dimezone-S which is a more stable form of phenidone.

One thing worth mentioning is that I had also designed a very interesting prototype, GVM1 prototype #5. This prototype was less active than the final version, and had a different alkali buffering system involving TEA. This developer exhibited exceptionally smooth grain without compromising on resolution and sharpness. I may eventually look at this formula more to make a GVM2, but for now I’ll leave it only as a curiosity for someone else to research:

To make 500ml of working solution. Start with 400ml of water, hot recommended

0.7g sodium sulfite

3.5g sodium metaborate

8ml Triethanolamine 99% (low freeze grade)

0.04g potassium bromide (0.4ml of 10%)

0.3g sodium bicarbonate

0.4g glycin

4ml of Dimezone-S 1% (I believe was dissolved in 90% isopropyl alcohol)

Use directly. Developing for 14m at 75F resulted in FP4+@200 and T-Max 400@800. No other tests were made. Contrast was similar to GVM1 but it was overall slower in activity and had even more highlight compensation with over exposure, exhibited exceptionally smooth grain structure with high resolution

Top to 500ml with water

GVM1 Prototype #5. FP4+@200

GVM2 Prototype Formula

I’ve created this prototype formula I named GVM2. It is designed to be similar to GVM1 but with only the most easily available ingredients.

GVM2, prototype #1:

130ml water

6.1g sodium sulfite

25g sodium carbonate, monohydrate

0.3g sodium bicarbonate (recommend: 0.5g)

(slight heating makes this a lot easier to dissolve)

3.6g glycin (will not dissolve until adding alcohol. Make a slurry)

0.34g Phenidone-A (will not dissolve until adding alcohol)

20ml 91% isopropyl alcohol (drug store sourced)

Top to 200ml with water

Use as you would GVM1 but with double the amount of concentrate to make working solution. Dilution A is 40ml of concentrate to make 1L of water, dilution B is 60, and dilution C is 80

Color should be slightly more pale than GVM1. Exhibits the same oxidation color reaction as GVM1, so if the concentrate goes green or blue it should be considered untrustworthy

Behavior is very similar but slightly more active, thus the recommendation to add more sodium bicarbonate. I've only done one test run of this developer but will watch how this developer concentrate ages.. so basically I provide this formula without any guarantee. It exhibits the same smooth yet sharp grain effect, gives slightly thicker max density, has the same extreme compensation effect, and the same peculiar contrast curve. It may give higher sharpness and/or better edge effects. However, it does not seem to give as much of a speed increase as GVM1 gives, potentially due to using only sodium salts. FP4+@400 test shots specifically give shadow details that are decent density but then fall off into dmin very rapidly, whereas in GVM1 this was not the case. I also doubt that the shelf life will be nearly as good due to phenidone's easy rate of ring breakage in alkaline solution and due to the lower sulfite concentration of the concentrate.

A test of GVM2 Prototype #1 using dilution A, 70F, 12m for development resulted in FP4+@200 and Ultrafine Extreme 100@400

Further Reading

Interesting reading for further research of phenidone-glycin developers: (russian, but pretty readable through google translate) : forum link, US Air Force patent There’s likely many more things to look up from these leads.

The combination of glycin and phenidone is an especially interesting one, and one which I believe is much undervalued in the modern world. Phenidone based film developers have definitely proven to be the most difficult developer to design I’ve ever messed with. However, the unique results presented by this unique design has proven to be worth the effort. I will definitely not be trying to formulate another phenidone film developer anytime soon, but it is definitely an interesting developing agent and one which requires very careful balancing and significant effort to produce a developer which produces an ideal contrast curve.

There is an active discussion on this developer design at Photrio with several photo chemists weighing in on comparisons to other known formulas: The formula for GVM1, a custom and unique phenidone-glycin film developer

Additional Images

If you try this developer and would like to contribute to this section, drop me an email at “ashley AT earlz dot net”